Don’t look now, but we’re in the wilderness. How so? Stay tuned.

Bamidbar is a complex book. On first reading, it can even seem disorganized. At heart, it is a story of failures and mistakes.

Well.

It’s an assemblage of laws, narratives and stories that move in and out of time—and the content is often downright depressing. But it is a book that rewards patience and reveals itself slowly. In the end, it is about spiritual transformation.

In Exodus, there is a monological relationship with God. It’s a one way street. God performed miracles and we watched. God spoke from Sinai, we received the message. The focus of this kind of communication—the monologue—is neither the listener nor their needs, the focus is on the message and purpose of the speaker. They speak, we listen.

Yes, I’m fully aware of the irony of explaining it…this way…but bear with me.

In Numbers—and even Leviticus to some extent—this opens into a dialogue with the Transcendent. Each party is both speaker and listener. Each party knows when to play which part. And each party listens to understand before responding.

That’s the key word. Mutual understanding is key—and through this, mutual respect is built. The focus is not on a monologue, a one way street, but a give and take, back and forth, call and response. Speaking, listening, and understanding. It is about building a relationship. In fact, the heart of Numbers is the Tent of Meeting—the Ohel Moed—the place where God and Israel come together.

If Exodus was about freedom “from”—from Pharoah, from slavery, from suffering—then in the words of Rabbi Jonathan Sacks (Z’L), Numbers is about freedom “to.”

To what? What is the point of this freedom? “So that they may worship me,” yes, but also that they may be in the presence of the Lord. That they may build a relationship with the Lord.

It’s an attempt to form a society which requires responsiveness and self-restraint, cooperation, respect and trust. But getting there is the challenge! If you thought the physical journey was difficult, the metaphysical one may be even harder!

In this book, the people of Israel are the problem. They are their own worst enemy. (I’m sure we can all relate…) God removed the tyrant from without—that was the easy part. Now, they have to remove the tyrant from within. As my professor Dr. Job Jindo would say, they needed to defeat the Pharaoh within. They may have left Egypt—but Egypt did not leave THEM!

Who is the Pharaoh of today? What is our wilderness? Is it privilege? Entitlement? Is it the ability to go home and close our door to the outside world, the greater community, and shut them out? To look at the news and think, “That won’t happen to me.” Or “There are plenty of people to help, I don’t need to contribute.” Or “Someone else will take care of it.” What holds us back from community, from helping? What frees us to join in?

There is no shortcut to liberty, no ready-made community or trust. These always require work and effort. At times, it can seem like years of slogging through a harsh land. Whether personal or societal, it is a long walk to freedom, trust, and community.

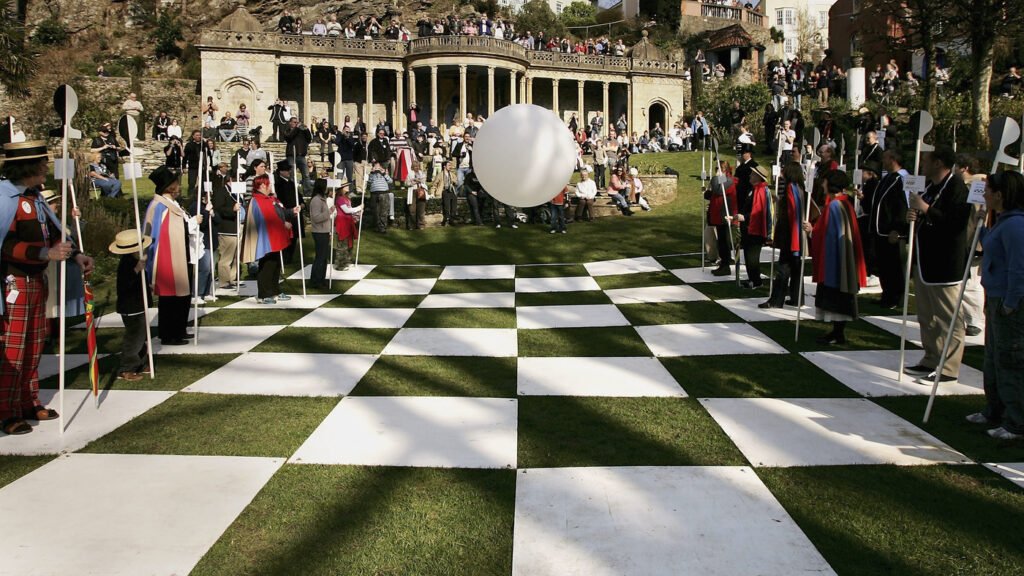

How many of you remember the tv series “The Prisoner”? It was about a former secret agent taken away to a place called The Village—how innocent, how anodyne—where he is given the number Six and a comfortable apartment where he is, yes, held prisoner until he reveals why he resigned.

Number Six fights against this—“I am not a number, I am a free man!” This is not his community, it is not where he belongs. He holds on to his identity fiercely, but we the viewers only ever know him by this number. We know nothing of his life before imprisonment or after his eventual release. These are secrets he does not share with the Village—or the viewers.

What we see this week—and what Bella is going to teach us more about tomorrow—is a series of names to start the census. Each male of fighting age, is counted—except the Levites—and the leaders are identified by name and tribe. They aren’t anonymous brick-makers or prisoners. They are no longer numbers, no longer slaves. They are free men, restoring their humanity name by name. Tribe by tribe. Flag by Flag. They are building their culture, their community, their freedom. Only when we find our tribe, only when we link ourselves to our collective can we make culture and meaning as individuals and together as a group.

As for our societal wilderness, well. The last few weeks, we’ve seen that in stark relief. Upstate New York. Texas. Oklahoma. California. Lists of names we’ll never know as anything more than memorials. Numbers of casualties with updated totals each week. This is where numbers lose meaning and identity, we don’t process them as people let alone losses.

And these outposts of the wilderness, these are vital parts of every community, not just schools but synagogues, churches, hospitals, grocery stores. These incidents are designed to shatter community, to send us into hiding, into fear.

Are we numbers, or are we names? Are we prisoners with secrets in comfortable apartments? Or are we sacred makers of meaning, pillars of community? Are we just listening to a monologue—well, yes, but you know what I mean—or are we seeking dialogue? Are we helpers, or are we waiting for help?

You decide. I mean that. We each can only decide for ourselves. As my peloton instructor says, “I make suggestions. You make decisions.”

I’d like to think I’m preaching to the choir. You’re here, aren’t you?

Let me leave you with this. What did we do in the desert? What was it all for? We carried God with us. We held signs and standards high. We trooped in unison. Yes, we failed and failed again. That’s life. But we got up, we kept going. We were the heavenly chariot, God’s army on earth.

We can be still.

But only together. In community.