One thing I’ve learned here in the High Country is that the weather is… unpredictable. You’ve heard the line, “If you don’t like the weather, just wait,” right? You’ll need a sweater in July, but you’re fine to go swimming in September. A morning that starts in the 40s can reach the high 70s by lunchtime. So now, I dress in layers and carry an umbrella at all times. I’m learning.

A few weeks ago, it was a warm Friday, and the air conditioning was set low to cool the building down. Apparently, this was too cold for someone, and, in the middle of worship, they went and turned up the temperature — so much so in fact that the heat clicked on. Guys, I’ll confess, I started sweating. And I wasn’t sure why at first.

After fifteen minutes or so, someone else got too warm and went back to turn the thermostat back down. I bring this up not to blame anyone, its just that everyone wanted something different. We all want to be comfortable, but each of us has a different level of comfort. Some may be closer on the warm side, some closer on the cold, and some might fall right in between.

Now, I kept singing and praying through the sweat and the chills as the drama played out, but inside, I was cracking up. Because I thought, “This is going in a sermon. And I think I know which one.” Lo and behold, here we are.

The lesson — in a community, it can be hard to make everyone happy all at once.

Ours is a varied community. We are made up of different ages, genders and sexual identities, and economic situations. We have single members, widowed members, and a growing number of young families. We live in different towns and counties, some nearby, some quite distant. We have college students that bring life and energy, and seniors who bring wisdom and strength. Many of us live here year-round, but many have winter homes in warmer climes. For many, this is our sole spiritual home, but a fair percentage attend and support synagogues elsewhere.

With all these differences, how can we continue to be a kehillah kedosha – a holy community? How can we get the temperature right? Such a simple question, but not such a simple answer. Since we’re Jewish, and I’m a rabbi, let’s go to the Tanach and our Sages to guide us.

Moses has a problem. The Israelites were redeemed by God from Egypt and now, according to our Sages, some two million people are depending on him to manage their disputes and problems. He sits from evening to morning trying to adjudicate. And you thought the line at Motor Vehicles was long!

Next thing you know, a leadership consultant shows up. McKinsey on a camel. His name is Yitro, also known as Moses’ father-in-law. He has experience in this kind of thing, he was the High Priest of the Midianites. They were a nomadic people, distantly related, who likely numbered in the hundreds of thousands. Yitro had heard about the Exodus and went to his son-in-law to see what was what.

We read in Exodus 18:14:

But when Moses’ father-in-law saw how much he did for the people he said, “What is this thing that you are doing to the people? Why do you sit as a magistrate alone, while all the people stand about you from morning until evening?”

Let’s look more closely at this line, “kol asher hu oseh la’am.” One translation is, “what he did for the people,” but I prefer another teaching from Rabbi Shaya Katz: “what he was doing TO the people.” They were the victims! From this perspective, Yitro wasn’t that worried about Moshe. He saw the people waiting in line day and night, looking for answers — THEY were the ones who needed help! What on earth was Moses doing to them?

In verse 16 Moses tries to explain himself:

When they have a dispute, it comes before me, and I decide between one party and another, and I make known the laws and teachings of God.

“Bein ish uvein re-eihu.” Between a person and their fellow. Two people are in a dispute and Moses must say who is right and who is wrong. Yitro continues his advice:

You shall enlighten them as to the statutes and laws and impart to them the path in which they must walk, and the deeds they must do.

In the Talmud, the rabbis deconstruct this line, וְאֶת־הַֽמַּעֲשֶׂ֖ה אֲשֶׁ֥ר יַעֲשֽׂוּן “deeds they must do” into two parts. “Deeds” means judging according to the strict interpretation of law. “That they must do” means going beyond the letter of the law. Moses’ harsh legal rulings are hurting the people, his stringency is a danger to the community.

Our sages, like Yitro before them, understood the importance of seeing beyond black and white. To build a healthy, thriving community, there must be flexibility and compassion. There must be room to go beyond stricture. There must be space for compromise.

The judges of First Century Jerusalem were so machmir, so picayune in legal issues, that their failure to create compromises with litigants led to the destruction of the city of Jerusalem. They did only what they needed to do, nothing more. They didn’t, wouldn’t — and maybe couldn’t — see the bigger picture.

How important is compromise? In the Shulchan Aruch, the definitive compilation of Jewish law, we are told that even in cases where a judge knows one party owes another party money — let’s say Sherl owes Berl 100 kopeks, plain as day, no question of who is in the right, and the dayan is about to bring the ruling — even THEN it is a mitzvah to attempt a settlement. Both parties should walk away feeling that they gained something.

For Jews, it is a mitzvah to compromise. Why? Because the needs of a civil society are greater than the need for black and white judgement. Maybe you’ve heard this line from Star Trek: “The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few.” Civil peace trumps din, strict judgement. Part of being a healthy community means maintaining equilibrium. Part of living in a community involves maintaining relationships.

If Berl and Sherl both walk away feeling that, while they didn’t get everything they wanted, they are basically happy with the solution, then perhaps one day they will reconcile. He got his, but I got mine. Let’s reach out and mend fences. Maybe they’ll invite one another to a Shabbes meal. Maybe they’ll attend a wedding of one another’s children. Keeping the peace between us is more important than being right or wrong.

I’ve heard stories about members of various synagogues who don’t get their way and simply walk out the door. As the saying goes, they take their toys and go home. I’ve known temple members who pitch angry fits at temple staff if something is not to their liking. I’ve heard of grudges between congregants that spiral through the spiritual home, people choosing sides. This kind of thinking destroyed Jerusalem. It brought down cities and temples.

Dr. Scott W. Sunquist, the President of Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, recognizes this as well:

Whether it be out of insecurity, idolatry, or egoism, our leaders and the general population seem to think that every decision is either good or bad; right or wrong. But this is flawed reasoning and simply not true. People seem to have a hard time with nuance and compromise today, but our fallen world is filled with nuance and compromise. Decisions are better or worse, but seldom is a decision absolutely good.

The decisions I make may make life better for many people and for the institution but still hurt or displease some people.

He teaches about what he calls “holy compromise,” something he considers a necessity.

Without surrendering our core beliefs, we must be able to reach out to connect with others to find common ground — not my ground or your ground. All communities in this fallen world must be based on holy compromise. Holy because it recognizes the One above all who knows all…and compromise because that holy love makes it possible to give up or sacrifice some of my desires for a greater good: community.

Think about it. We are all in our camps, even our own siloes. Red or Blue. Year-round residents or snowbirds. Town or gown. Often, we watch and listen only to those who agree with us, villainizing the other. We lean into confirmation bias and avoid challenging our own assumptions.

Some activists railed against the “Mr. Potato Head” toy. They claimed he was sending a sexist message. And so, in 2021, Hasbro changed the brand name to just “Potato Head.” Some claimed victory even though the line does still include specific “Mr. Potato Head” and “Mrs. Potato Head” toys as part of the line to this day.

On the other side that year, there was a rumor that gas stoves would be banned, leading to an explosion of misplaced outrage and hashtags like “Save our Stoves!” No one was taking the stoves! Do you still have a gas stove at home? Has anyone come by to take it away?

No one was eating the cats or dogs in Ohio either! Portland isn’t a wartorn ruin! And so on.

We can be quick to dig in, to wallow in confirmation bias, and get stuck. It is sometimes hard to see nuance, to appreciate the complexity of the other. Like Moses, we are judging strictly and harshly, reducing everything to right and wrong, black and white. There is no grace. There is no willingness to find middle ground.

That is no way to run a household, a country…or a shul.

Let me tell you about the founder of the Visa card, Dee Hock.

At its founding, it was an important innovation. Or it would be. Its founding was far from a sure thing. Negotiations were held up, there were multiple points of contention — long story short, there were three deal-breaking disagreements standing in the way. Things were at an impasse.

Late in the second year of negotiations — you heard that right, the second year — Hock called a summit of all the international banks that would potentially work together to build this organization…or go their separate ways.

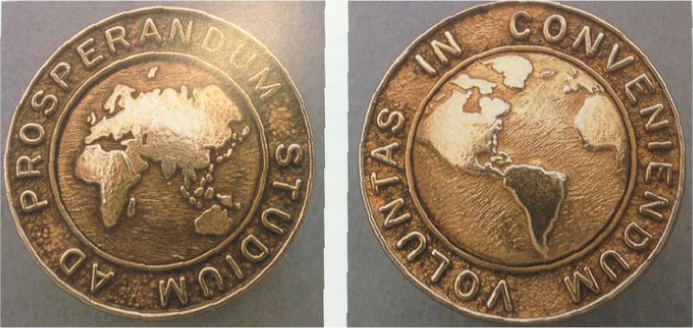

He and his team had an idea. They commissioned a jeweler to make cufflinks for each member of the organizing committee. On one cufflink the Latin phrase “Studium Ad Prosperadum” was set around half of the Earth. On the other, around the other half of the Earth read “Voluntas In Conveniendum”.

In other words, on one hand: “The will to succeed”

And on the other hand: “The grace to compromise”

So there they are at dinner — the next morning would be the final vote, either they work together or the whole thing collapses. As they sat down, each found a small jewel box at their place setting.

Dee Hock stood. “We meet tomorrow for the final time. There is no possibility of agreement. But I have one last request. Please wear these cufflinks to the meeting. When we part, let them be a reminder that the world can never be united through us because we lack the will to succeed and the grace to compromise.” He paused for effect and then…

“If, by some miracle, our differences dissolve before morning, let them remind us instead that the world was united because we did have the will to succeed and the grace to compromise.”

The room was so quiet, you could have heard a pin drop. No. You could have heard the pin pierce the air as it dropped.

And then, out of nowhere, someone shouted, “You miserable…” — let’s say “so and so” — and the room dissolved in laughter. The dam broke, the ice melted.

That next morning, each banker did wear their cufflinks. Within one hour, they had reached agreement on every issue. Every holdout reversed course, and they all voted in the affirmative. A few months later the international organization that became VISA International came into being.

To build greatness, even right here in Boone, we must look at the larger picture, we must give grace in order to receive it. To build a holy community, we need holy compromise. Before you send an angry message, take a moment to cool off. Before you call that one friend to complain about this or that, take a breath. Before you lash out in anger, try to see the other’s position. We don’t have to raise the temperature, and we don’t have to freeze anyone out.

It may not be easy, but you must try. That’s part of being a community.

Look at the wall now. Right over there. Yes, there’s a locked box on the thermostat now. Yes, I asked for it. Blame me. After all, I’m the one up here, sweating in this robe to serve you.

If you run cold, maybe bring a sweater or scarf. If you feel warm, maybe dress in layers you can remove if need be. It’s a small thing, but it’s a start. I’m in layers, umbrella ready. As I said, I’m learning.

“The will to succeed”

“The grace to compromise”

Together, as one family, we will thrive, grow, and find peace here in the High Country and beyond.

And let us say, Amen v’Amen.